Underwater inspection drones, commonly referred to as Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), represent a significant advancement in the field of subaquatic examination, particularly for critical infrastructure. These unmanned, tethered or untethered vehicles are equipped with a range of sensors, cameras, and manipulators, enabling them to perform detailed inspections in environments inaccessible or hazardous to human divers. The application of ROVs spans various industries, including oil and gas, renewable energy, civil engineering, and maritime archaeology. Their ability to operate in deep, dark, and often turbulent waters without the physiological limitations of human divers positions them as an invaluable tool for maintaining the integrity and safety of submerged assets.

The operational principle of an ROV involves a control unit, typically located topside on a vessel or land, communicating with the underwater vehicle. This communication link, often a fiber optic umbilical, transmits power, data, and video signals, allowing an operator to pilot the ROV, control its instruments, and receive real-time feedback. The design of ROVs varies widely, from compact, easily portable units for shallow water inspections to large, heavy-duty work-class ROVs capable of complex intervention tasks at extreme depths. This versatility makes them adaptable to a broad spectrum of inspection requirements.

The increasing complexity and aging of global submerged infrastructure, coupled with a growing emphasis on safety and environmental protection, have spurred the development and adoption of ROV technology. Traditional inspection methods involving human divers are inherently limited by depth, bottom time, and the risks associated with underwater operations. ROVs mitigate many of these risks, offering a safer, often more cost-effective, and consistently repeatable method for data acquisition. As you delve into the capabilities of these machines, consider them as extensions of human perception, allowing us to see and interact with the underwater world without direct physical presence.

Historical Context and Evolution

The lineage of ROVs can be traced back to the early 1950s, with the development of initial tethered underwater vehicles for military applications, primarily for mine countermeasures and torpedo recovery. These early prototypes were rudimentary, lacking the sophisticated imaging and maneuvering capabilities of modern ROVs. The breakthrough came with the integration of video cameras and more precise propulsion systems, transforming them from simple recovery tools into viable inspection platforms.

The 1970s marked a period of rapid development, particularly driven by the burgeoning offshore oil and gas industry. As exploration moved into deeper waters, the limitations of human divers became more pronounced, creating a demand for technology capable of operating beyond saturation diving depths. This era saw the emergence of commercial ROVs designed for pipeline inspection, platform maintenance, and wellhead intervention. Manufacturers began to focus on modular designs, allowing for the easy integration of various sensors and tooling packages tailored to specific tasks.

The last few decades have witnessed an exponential growth in ROV capabilities, fueled by advancements in computing power, sensor technology, and battery life for untethered variants. Miniaturization has led to the proliferation of observation-class ROVs, accessible to a wider range of users, from scientific researchers to recreational enthusiasts. Simultaneously, the work-class ROV sector has pushed the boundaries of depth and intervention capability, with vehicles now capable of operating thousands of meters deep and performing intricate construction and repair tasks. This journey from rudimentary prototypes to sophisticated autonomous systems highlights a continuous drive to overcome the challenges of the underwater environment.

Underwater inspection drones, also known as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), are revolutionizing the way we assess and maintain critical infrastructure beneath the water’s surface. These advanced technologies provide real-time data and high-resolution imagery, making them invaluable for inspecting bridges, pipelines, and underwater structures. For those interested in exploring how technology enhances business operations, a related article on the best tablets for business in 2023 can be found here: Best Tablets for Business in 2023. This resource highlights the tools that can support professionals in various industries, including those utilizing ROVs for underwater inspections.

Types of Underwater Inspection ROVs

The ROV landscape is diverse, characterized by a range of designs optimized for specific operational profiles and depths. Understanding these classifications is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool for a given inspection task. The primary differentiation often lies in their size, power, and tooling capabilities, directly influencing their operational depth, maneuverability, and the complexity of tasks they can undertake.

Observation-Class ROVs

Observation-class ROVs represent the entry point into the world of underwater robotics. These vehicles are typically compact, lightweight, and highly portable, designed for visual inspections, data collection, and light intervention tasks. Their smaller size and often lower power consumption make them ideal for shallow water applications, confined spaces, and situations where rapid deployment is paramount. Think of them as the nimble scouts of the underwater world, able to navigate tight passages and provide a general overview.

Common applications for observation-class ROVs include dam inspections, harbor facility assessments, bridge pier examinations, and aquaculture net monitoring. They are frequently equipped with high-definition cameras, LED lights, and sometimes basic sonar for navigation in murky waters. Some models may also carry simple manipulators for retrieving small objects or deploying sensors. Their tethered nature ensures continuous power supply and real-time data transmission, crucial for maintaining situational awareness during an inspection. The ease of operation and relatively low cost of these systems have democratized access to underwater inspection capabilities for a wider range of organizations.

Light Work-Class ROVs

Stepping up in capability, light work-class ROVs bridge the gap between simple observation units and heavy-duty intervention vehicles. These ROVs are generally larger and more powerful than their observation counterparts, capable of carrying a greater payload of sensors and tooling. Their increased thrust allows them to operate in stronger currents and at greater depths, extending their utility to more demanding inspection and light intervention tasks.

Light work-class ROVs often feature more sophisticated navigation systems, including more precise altimeters and Doppler Velocity Logs (DVLs), enabling more accurate positioning and automated flight paths. They can accommodate multi-beam sonars, sub-bottom profilers, and various non-destructive testing (NDT) sensors such as cathodic protection (CP) probes or ultrasonic thickness gauges. Their manipulators are also more robust, capable of performing tasks like valve turning, debris removal, and sensor deployment. These ROVs are frequently employed in pipeline surveys, subsea structure inspections for oil and gas or wind farms, and light construction support, acting as the versatile generalists in an underwater toolbox.

Heavy Work-Class ROVs

At the pinnacle of ROV capability are the heavy work-class vehicles. These are large, powerful machines designed for highly complex intervention tasks in deep water and harsh environments. They are the workhorses of the subsea construction and maintenance industry, capable of deploying and operating a wide array of heavy tooling and performing intricate tasks that would otherwise require highly specialized human diver operations, if even possible.

Heavy work-class ROVs are characterized by their significant thrust, enabling them to maintain position in strong currents and lift heavy loads. They typically feature multiple powerful manipulators, capable of precision cutting, grinding, welding, and detailed component manipulation. Their payload capacity allows for the integration of advanced acoustic imaging systems, high-resolution cameras, laser scanners, and a comprehensive suite of NDT equipment. These ROVs are indispensable for offshore oil and gas field development, subsea manifold installation, cable laying and burial, and emergency repair operations. Their deployment often requires dedicated vessels with specialized launch and recovery systems, reflecting their significant operational footprint. They are, in essence, the brute force and precision artists of the deep, executing complex and critical tasks with unyielding resolve.

Key Technologies and Sensor Suites

The utility of an underwater inspection ROV is directly proportional to the sophistication and diversity of its integrated technologies and sensor suites. These components are the eyes, ears, and hands of the ROV, gathering the data necessary for comprehensive infrastructure assessment. As you consider the data gathering capabilities, think of these sensors as providing a multi-spectral window into the health of submerged assets.

Imaging and Lighting Systems

Visual inspection remains a cornerstone of ROV operations. High-definition (HD) and ultra-high-definition (UHD) cameras provide operators with a clear, real-time view of the inspection area, allowing for the identification of anomalies such as cracks, corrosion, marine growth, and structural damage. Modern ROVs often incorporate multiple cameras, including zoom cameras and low-light sensitive cameras, to adapt to varying underwater conditions.

Effective lighting is paramount in the dark underwater environment. LED lighting arrays provide powerful and energy-efficient illumination, minimizing power consumption while maximizing visibility. The placement and intensity of these lights are carefully considered to reduce backscatter and maximize the clarity of the captured imagery. Some advanced systems also utilize specialized lighting, such as structured light or laser projection, for precise three-dimensional modeling and measurement of objects. The quality of the visual data dictates the accuracy of many subsequent analyses, making these systems critical.

Acoustic Sensors (Sonar)

When visibility is poor, or when detailed topographical information is required, acoustic sensors, or sonars, become indispensable. Sonar systems emit sound waves and interpret the echoes to create images or maps of the underwater environment, much like bats perceive their surroundings. There are several types of sonar systems commonly employed on ROVs, each serving a distinct purpose.

- Multibeam Sonar: This technology emits multiple narrow beams in a fan shape, allowing for the rapid creation of high-resolution 3D bathymetric maps and imagery of the seabed and submerged structures. It is crucial for detailed site surveys, pipeline routing, and identifying anomalies on the seafloor.

- Side-Scan Sonar: Side-scan sonar provides a wide-area acoustical image of the seabed features. It is excellent for detecting objects lying on the seafloor, such as pipelines, cables, or debris, and is often used for reconnaissance and target detection over broad areas.

- Sub-Bottom Profiler: This sonar system penetrates the seabed to image geological layers below the surface. It is vital for identifying buried pipelines, assessing sediment thickness, and geological surveys prior to construction.

- Obstacle Avoidance Sonar: These forward-looking sonars help the ROV navigate safely by detecting obstacles in its path, particularly useful in cluttered environments or low-visibility conditions.

Navigation and Positioning Systems

Accurate navigation and positioning are fundamental for effective ROV operations. Knowing precisely where the ROV is in the three-dimensional underwater space, and where it has been, is crucial for mapping, repeatable inspections, and intervention tasks. GPS alone is ineffective underwater due to signal attenuation, necessitating specialized acoustic and inertial navigation systems.

- Ultra-Short Baseline (USBL) and Long Baseline (LBL) Acoustic Positioning Systems: These systems use transponders deployed on the seabed or towed from a surface vessel to precisely determine the ROV’s position relative to a known reference point. USBL is more common for quick deployments, while LBL offers higher accuracy over a defined area.

- Inertial Navigation Systems (INS) / Doppler Velocity Logs (DVL): An INS, often coupled with a DVL, provides highly accurate real-time position, velocity, and attitude (pitch, roll, yaw) data, independent of external acoustic signals. DVLs measure the ROV’s velocity relative to the seabed by emitting sound pulses, making them crucial for precise maneuvering and station-keeping.

- Pressure Sensors and Altimeters: These provide depth information and height above the seabed, essential for maintaining standoff distances during inspections and avoiding collisions with the bottom.

Non-Destructive Testing (BDT) and Environmental Sensors

Beyond visual and acoustic mapping, ROVs can carry a suite of sensors for non-destructive testing (NDT), allowing for the assessment of material integrity and environmental conditions without causing damage to the infrastructure. These sensors delve beneath the surface, revealing issues that visual inspection alone would miss.

- Cathodic Protection (CP) Probes: Used to measure the electrical potential difference on metallic structures, CP probes assess the effectiveness of cathodic protection systems designed to prevent corrosion. This is vital for pipelines, platforms, and other steel structures.

- Ultrasonic Thickness Gauges (UTG): These sensors measure the wall thickness of metallic structures, identifying areas of material loss due to corrosion or erosion. This data is critical for structural integrity assessments.

- Manipulators and Tooling: While not sensors themselves, ROV manipulators are capable of deploying and operating a variety of NDT sensors directly onto the infrastructure, as well as performing tasks like cleaning marine growth to expose inspection areas.

- Environmental Sensors: ROVs can carry sensors for measuring water temperature, salinity, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, and hydrocarbon levels. This data is important for environmental monitoring, assessing potential impacts of infrastructure, and understanding the conditions in which assets operate.

Applications in Infrastructure Inspection

The unique capabilities of underwater inspection ROVs have transformed the way critical submerged infrastructure is monitored and maintained. Their ability to access challenging environments, collect diverse data sets, and operate safely and efficiently makes them an indispensable tool across numerous sectors. Consider the ROV as the tireless sentinel, perpetually vigilant over our submerged assets.

Oil and Gas Infrastructure

The offshore oil and gas industry was an early adopter and continues to be a primary driver of ROV technology. Inspection of subsea pipelines, wellheads, manifolds, and production platforms is crucial for ensuring operational integrity, preventing spills, and extending asset lifespan. ROVs perform a litany of tasks in this sector:

- Pipeline Inspection: ROVs conducting pipeline inspections visually identify external damage, free spans, exposure, and corrosion. They can also deploy NDT sensors for detailed cathodic protection readings and ultrasonic thickness measurements to assess internal corrosion or erosion. Accurate positioning systems allow for precise mapping of pipeline routes and depth of burial.

- Platform and Risers: Legs, cross-members, and risers of offshore platforms require regular inspection for fatigue cracks, corrosion, marine growth buildup, and structural deformation. ROVs can perform close visual inspections, often cleaning specific areas with brush attachments to facilitate detailed NDT measurements.

- Wellhead and Manifold Monitoring: These complex subsea systems demand frequent checks for leaks, valve integrity, and general condition. ROVs can precisely navigate through intricate structures, providing critical visual and sensor data for operational assurance.

- Debris Survey and Clearance: ROVs are used to survey the seabed for debris that could interfere with operations or damage infrastructure, and work-class ROVs can be deployed with manipulators to clear such obstructions.

Renewable Energy Infrastructure

The burgeoning offshore renewable energy sector, particularly wind farms, relies heavily on ROVs for inspection and maintenance. The dynamic environment and robust structures present unique challenges that ROVs are well-suited to address.

- Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations: Monopiles, jacket foundations, and floating foundations require regular visual inspection for fatigue cracks, scour around the base, corrosion, and the integrity of grout connections. ROVs provide detailed imagery and NDT data on these critical components.

- Subsea Cables: The power export cables connecting wind turbines to substations and to the onshore grid are vulnerable to damage from fishing activity, currents, and anchor drops. ROVs are used to inspect the burial depth of these cables, identify exposed sections, and assess any external damage. They can also aid in cable repair operations.

- Wave and Tidal Energy Devices: As these technologies evolve, ROVs will play an increasing role in inspecting their structural integrity, mooring systems, and connections in challenging tidal environments.

Civil Engineering and Port Infrastructure

Coastal and inland civil infrastructure, from bridges and dams to ports and harbors, necessitates regular underwater inspection to ensure public safety and operational continuity. ROVs offer a non-disruptive and safer alternative to human divers in many of these scenarios.

- Bridge Pier and Foundation Inspection: ROVs can meticulously inspect bridge piers, abutments, and foundations for scour, cracks, spalling, rebar exposure, and other structural degradation. Their ability to navigate in turbid water with sonar provides critical information when visibility is poor.

- Dam and Reservoir Inspection: Dams are vital for water management and power generation. ROVs inspect dam faces, intake structures, sluice gates, and trash racks for damage, sediment buildup, and operational integrity. They can operate in confined spaces and deep water, reducing the risks associated with diving.

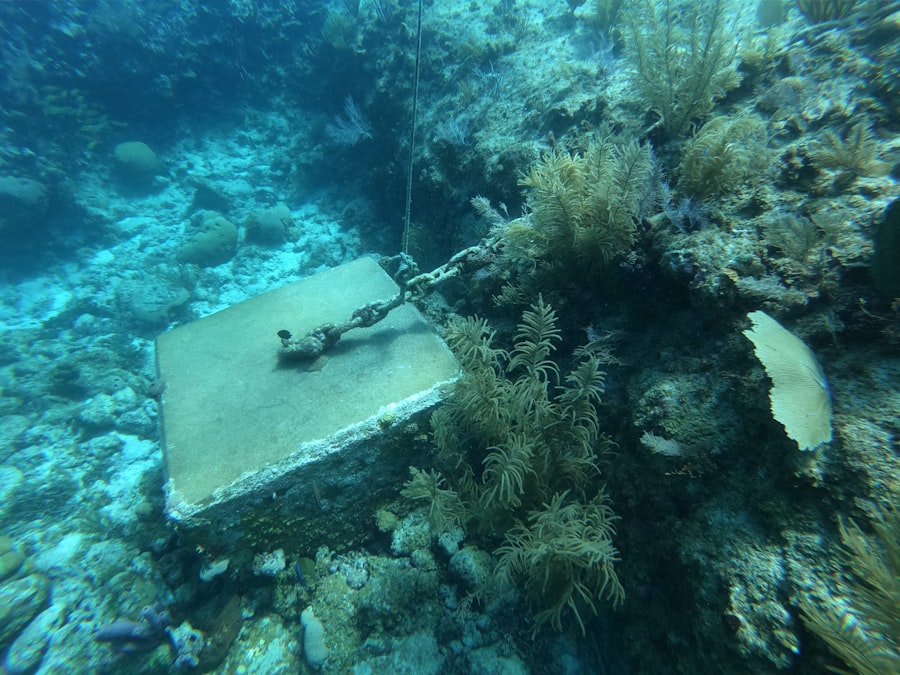

- Port and Harbor Facilities: Wharves, jetties, bulkheads, and quay walls are constantly exposed to corrosive seawater and mechanical stress. ROVs inspect these structures for cracking, deterioration of timber piles, corrosion of steel components, and general structural health. They can also survey the seabed for debris in shipping lanes.

- Underwater Tunnel Inspection: While more specialized, compact ROVs can be deployed within flooded tunnels to inspect linings, detect leaks, and assess structural integrity, minimizing the need for dewatering.

Other Specialized Applications

Beyond the primary infrastructure sectors, ROVs contribute to a myriad of other specialized underwater inspection needs:

- Desalination Plants and Intake Structures: Inspection of water intake screens and pipelines for blockages, biofouling, and structural damage is critical for efficient operation.

- Nuclear Power Plant Cooling Water Intakes: Ensuring the integrity of cooling water systems is paramount for safety, and ROVs provide a secure method of inspection in potentially hazardous areas.

- Marine Archaeology: While not infrastructure in the traditional sense, ROVs are invaluable for non-intrusive survey and documentation of underwater archaeological sites and shipwrecks, acting as remote historians.

Underwater inspection drones, also known as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), have become essential tools for assessing the integrity of underwater infrastructure. These advanced technologies allow for detailed inspections of bridges, pipelines, and other submerged structures, ensuring safety and efficiency in maintenance operations. For those interested in exploring the innovative applications of software in enhancing ROV capabilities, a related article can be found here, which discusses how software solutions can streamline data processing and visualization in underwater inspections.

Challenges and Future Developments

| Metric | Description | Typical Range / Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Operating Depth | Maximum depth the ROV can safely operate | 100 – 3000 | meters |

| Battery Life | Duration the ROV can operate on a single charge | 2 – 8 | hours |

| Payload Capacity | Maximum weight the ROV can carry for sensors or tools | 5 – 50 | kilograms |

| Camera Resolution | Quality of video feed for inspection | 1080p – 4K | pixels |

| Navigation Accuracy | Precision of ROV positioning underwater | 0.1 – 1.0 | meters |

| Speed | Maximum travel speed of the ROV | 1 – 3 | knots |

| Communication Range | Maximum distance for remote control and data transmission | 500 – 2000 | meters |

| Inspection Duration | Typical time for a single inspection mission | 1 – 6 | hours |

| Weight | Total weight of the ROV unit | 10 – 100 | kilograms |

| Operating Temperature Range | Temperature range in which the ROV can function | -10 to 40 | °C |

While ROVs have revolutionized underwater inspection, their widespread adoption and capabilities still face inherent challenges. Addressing these will be key to further unlocking their potential, particularly as the demand for subsea monitoring continues to increase. Looking ahead, consider the ROV not just as a tool, but as a platform for continuous innovation.

Operational Challenges

Despite their advancements, ROV operations are not without complexities and critical limitations:

- Turbidity and Visibility: In many coastal and freshwater environments, water clarity is consistently poor, severely limiting the effectiveness of visual inspections. Acoustic imaging systems mitigate this, but direct visual confirmation of small defects remains challenging.

- Strong Currents: While work-class ROVs are designed to operate in challenging currents, exceptionally strong flows can impede maneuvering, drain battery life (for untethered ROVs), and even risk vehicle loss. Precise thruster control and advanced propulsion systems are continuously under development to counteract this.

- Complex Geometries and Confined Spaces: Intricate structures or very confined spaces can be difficult for larger ROVs to navigate. While smaller observation-class ROVs are well-suited for such tasks, they often lack the tooling or sensor payload capacity of their larger counterparts.

- Tether Management: For tethered ROVs, managing the umbilical in dynamic environments or around complex structures is a significant operational challenge. Entanglement or damage to the tether can result in loss of communication, power, or even the ROV itself. Self-managing tether systems and untethered options offer solutions, but bring their own challenges.

- Cost of Deployment: Large, work-class ROVs require specialized vessels and highly trained personnel, making their deployment a significant logistical and financial undertaking. This can be prohibitive for smaller projects or routine inspections.

Technological Advancements

The field of ROV technology is dynamic, with continuous innovation aimed at overcoming current limitations and expanding capabilities:

- Increased Autonomy: The holy grail for ROVs is greater autonomy. Current ROVs are primarily teleoperated. Future developments will see ROVs capable of executing complex inspection missions with minimal human intervention, navigating autonomously, avoiding obstacles, interpreting data, and even performing basic repairs. This shift from ROV to Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) for inspection purposes is already underway, particularly for long-duration seabed surveys.

- Enhanced Sensor Fusion: Integrating data from multiple sensors (visual, acoustic, NDT, chemical) in real time will provide a more comprehensive and robust understanding of infrastructure health. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms will play a crucial role in processing and interpreting this vast amount of data, identifying anomalies and predicting potential failures with greater accuracy.

- Improved Power and Propulsion Systems: Advances in battery technology, fuel cells, and even wireless power transfer will extend the operational endurance of untethered ROVs, allowing for longer missions and reducing reliance on frequent recovery for recharging. More efficient and powerful thruster designs will improve maneuverability and current-handling capabilities.

- Miniaturization and Swarm Robotics: Developing ultra-compact ROVs that can operate in very confined spaces, potentially in a swarm, could revolutionize inspections of internal pipes, small diameter conduits, and other inaccessible areas. A swarm of smaller, interconnected robots could cover larger areas more quickly and efficiently.

- Advanced Human-Machine Interface (HMI): Intuitive control systems, virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR) interfaces will simplify ROV operation, allowing operators to feel more immersed in the underwater environment and control the vehicle with greater precision and ease.

The future of underwater infrastructure inspection lies in a blend of these evolving technologies, creating more intelligent, persistent, and capable robotic systems. They are becoming more than just remote eyes; they are evolving into sophisticated partners in managing the health of our silent, submerged world.

FAQs

What are underwater inspection drones (ROVs)?

Underwater inspection drones, also known as remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), are unmanned submersible devices used to inspect and monitor underwater infrastructure such as pipelines, bridges, dams, and offshore platforms. They are controlled remotely by operators on the surface.

What types of infrastructure can underwater inspection drones inspect?

Underwater inspection drones can inspect a variety of infrastructure including underwater pipelines, bridge foundations, dams, offshore oil rigs, ship hulls, and underwater cables. They help detect damage, corrosion, and structural integrity issues.

What are the advantages of using ROVs for underwater inspections?

ROVs provide safer, faster, and more cost-effective inspections compared to human divers. They can operate at greater depths and in hazardous conditions, provide real-time video and sensor data, and reduce the need for costly shutdowns or manual inspections.

What equipment do underwater inspection drones typically have?

These drones are usually equipped with high-definition cameras, sonar systems, lighting, robotic arms for manipulation, and various sensors to measure parameters like pressure, temperature, and corrosion levels. Some models also have GPS and navigation systems.

How do operators control underwater inspection drones?

Operators control ROVs remotely from a surface vessel or control station using a tethered cable or wireless communication. They use joysticks, control panels, and video feeds to navigate the drone, capture images, and perform inspection tasks underwater.