This article examines active capture satellites, a proposed solution for mitigating space debris. The scale and implications of orbital debris necessitate a diverse range of strategies. Active capture satellites represent one such approach, focusing on the direct retrieval or deorbiting of defunct spacecraft and fragments.

Space debris, also known as orbital debris or space junk, encompasses non-functional human-made objects in Earth orbit. This includes spent rocket stages, defunct satellites, and fragments from collisions or anti-satellite weapon tests. The increasing population of such objects poses a significant threat to operational spacecraft and future space endeavors. Each piece of debris, regardless of size, carries substantial kinetic energy due to its orbital velocity. A small paint fleck, for instance, can inflict considerable damage upon impact with a satellite moving at tens of thousands of kilometers per hour.

The Kessler Syndrome

The most concerning implication of unchecked debris growth is the Kessler Syndrome. Named after NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler, this theoretical scenario posits a cascade of collisions. As the density of objects in a particular orbital region reaches a critical threshold, a collision between two pieces of debris generates more fragments. These new fragments then collide with other objects, creating even more debris, leading to an exponential increase in collisions. This renders particular orbital altitudes unusable for generations, effectively closing access to space. Understanding this potential future necessitates proactive measures. The current trajectory of debris accumulation suggests that passive mitigation strategies alone, such as designing satellites for deorbiting at end-of-life, may be insufficient.

Economic and Strategic Implications

The economic ramifications of space debris are substantial. Billions of dollars are invested in designing, launching, and operating satellites for communication, navigation, Earth observation, and scientific research. The threat of collision necessitates costly design features, insurance premiums, and the potential loss of vital infrastructure. Furthermore, countries with significant space assets face strategic concerns regarding the security and operability of those assets. The ability to guarantee access to and use of space is becoming increasingly critical for national interests. Effective debris removal could safeguard these investments and ensure the long-term viability of space exploration and utilization.

As the issue of space debris continues to escalate, innovative solutions such as active capture satellites are being explored to mitigate the risks associated with orbital clutter. A related article that delves into the broader implications of technology in addressing this challenge can be found at The Next Web, which provides insights into the advancements and strategies being developed to ensure a sustainable future in space.

Principles of Active Capture

Active capture, as a concept, involves sending a dedicated spacecraft to rendezvous with a piece of debris, secure it, and then alter its orbit, typically to facilitate its re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere for incineration. Unlike passive methods that prevent new debris, active capture directly addresses existing objects. This is a complex engineering challenge, akin to catching a bullet with a bullet while both are traveling at extreme speeds. The target debris is often uncooperative, meaning it may be tumbling, lacking power, or have an unpredictable trajectory. This necessitates precise maneuvers and sophisticated capture mechanisms.

Target Selection Criteria

The selection of debris targets is crucial for maximizing the impact of removal efforts. “High-value” targets are typically chosen based on several criteria:

- Mass: Larger objects contribute more to the overall debris mass and present a greater collision risk. Removing a single defunct satellite weighing several tons can have a more significant impact than removing numerous smaller fragments.

- Collision Risk: Objects in orbits with high population density or those predicted to have close approaches with operational satellites are prioritized.

- Orbital Altitude: Debris in heavily used orbits, such as Low Earth Orbit (LEO) between 600 and 1000 kilometers, or Geosynchronous Earth Orbit (GEO), often warrant more urgent attention.

- Uncertainty in Position/Trajectory: Objects with inaccurate orbital data pose a higher risk due to unpredictable movements.

- Economic Impact: The potential for a piece of debris to damage a critical operational asset.

Orbital Mechanics and Rendezvous Challenges

Executing a rendezvous and capture mission requires a detailed understanding of orbital mechanics. The active capture satellite must precisely match the orbit of the target debris. This involves numerous orbital maneuvers, including phase adjustments, plane changes, and fine-tuned approaches. Fuel consumption is a significant constraint, as each maneuver expends propellant. Furthermore, the rendezvous process is complicated by the potentially uncontrolled tumbling or rotation of the target debris. Specialized sensors, such as lidar and radar, are employed to determine the debris’s attitude and rotational rate, enabling the capture satellite to approach safely and autonomously. The time window for capture may be narrow, requiring real-time adjustments and decision-making capabilities.

Active Capture Technologies

Various technologies are under development or consideration for the physical capture and deorbiting of space debris. Each method presents its own advantages and challenges, and the optimal choice often depends on the characteristics of the target debris.

Robotic Arms

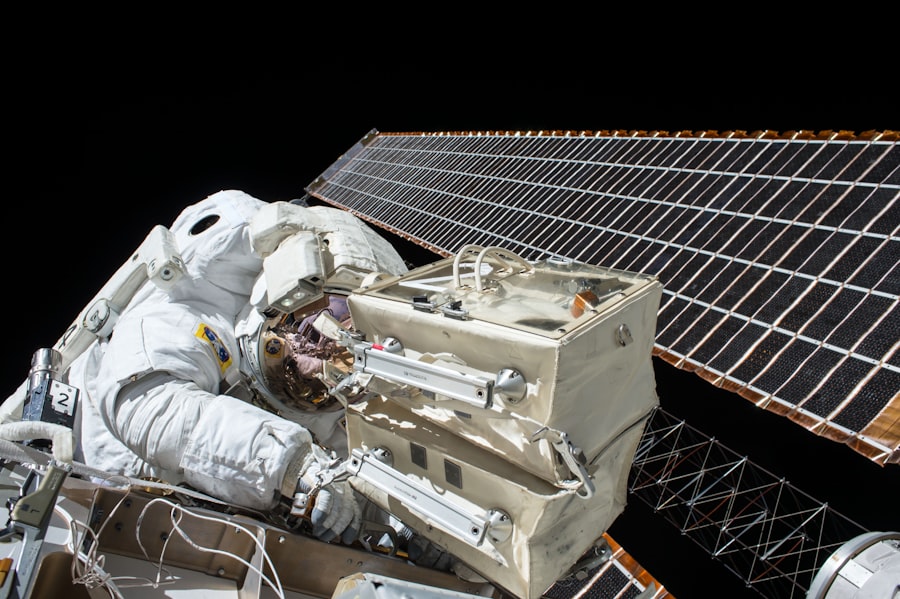

Robotic arms, similar to those used on the International Space Station (ISS), are a well-understood technology. The European Space Agency’s (ESA) e.Deorbit mission concept, for instance, explored the use of a robotic arm to grapple a defunct satellite. The arm would attach to a secure point on the target, such as a launch adapter ring or a designated grapple fixture, if available.

- Advantages: Mature technology, precise control, ability to handle cooperative targets, potential for inspection and repair.

- Challenges: Limited reach, difficulty with tumbling or unknown objects, requires a suitable grappling point, potential for damage to the arm or target. Robotic arm missions often require complex algorithms for path planning and collision avoidance, particularly with irregularly shaped or tumbling debris.

Nets

Net capture involves deploying a large net from the active capture satellite to ensnare the debris. Once captured, the net, along with the debris, can be deorbited. ESA’s RemoveDEBRIS mission successfully demonstrated net capture in orbit, targeting a deployed cubesat. Picture a fisherman casting a net; the principle is similar, but in the vacuum of space at hypervelocities.

- Advantages: Can capture tumbling or irregularly shaped objects, provides a large capture area, potentially simpler mechanism initially.

- Challenges: Risk of net entanglement with operational spacecraft or other debris, potential for uncontrolled tumbling after capture, difficulty in precisely deorbiting a large, irregular object, concerns about debris shed from the net itself. The net material must be robust enough to withstand the forces of capture and subsequent atmospheric re-entry.

Harpoons

Harpoons are another direct contact capture method. A projectile is fired from the active capture satellite into the target debris, tethering it for deorbiting. The RemoveDEBRIS mission also successfully tested a harpoon system. This is analogous to a whaler’s harpoon, but on scales of speed and precision far exceeding terrestrial parallels.

- Advantages: Effective for targets with robust structures, can penetrate coatings or solar panels, potentially simpler mechanism than a robotic arm.

- Challenges: Risk of fragmenting the target object upon impact, requires precise aim, potential for propulsion system contamination from target materials, difficulty with objects where penetration could cause further damage or release hazardous materials. The choice of harpoon design and impact velocity is critical to prevent fragmentation.

Tethers and Electrodynamic Tethers

Tethers can be used to connect an active capture satellite to a piece of debris, then either passively deorbit the combination or actively pull the debris into a lower orbit. Electrodynamic tethers (EDTs) leverage the Earth’s magnetic field. By deploying a long, conductive tether across magnetic field lines, an electric current is induced. This current interacts with the magnetic field to generate a Lorentz force, which can be used to either provide thrust (raising altitude) or drag (lowering altitude).

- Advantages: Potentially propellant-free deorbiting (for EDTs), scalable for different object sizes, can deorbit multiple objects in a sweep if designed appropriately.

- Challenges: Risk of breaking or tangling, requires the active capture satellite to maintain precise orientation, EDTs are sensitive to plasma conditions, long deployment times. The interaction of tethers with micro-meteoroids and atomic oxygen also presents durability challenges.

Economic and Policy Considerations

The implementation of active capture missions is not solely a technical challenge; it also involves complex economic, legal, and political considerations. The “tragedy of the commons” aptly describes space, where individual actors benefit from its use, but the cumulative effects of their actions (debris generation) degrade the environment for everyone.

Who Pays for Debris Removal?

One of the most significant hurdles is determining financial responsibility. The “polluter pays” principle, common in terrestrial environmental law, is difficult to apply in space. Identifying the generator of decades-old debris, particularly fragments, can be impossible. Even when the owner of a defunct satellite is known, their liability for debris cleanup is often unclear under current international space law. Options include:

- National Funding: Governments could fund removal missions for debris predominantly from their own space programs.

- International Collaborations: Pooling resources and expertise across multiple nations could enable larger-scale efforts.

- Commercial Ventures: Private companies could offer debris removal services, potentially paid for by satellite operators or insurers.

- “Space Tax” or Levy: A proposed system where a small fee is levied on each satellite launch or active satellite in orbit, contributing to a global cleanup fund. This mechanism could distribute the financial burden more equitably across the spacefaring nations.

Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

Current international space law, primarily the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and the Liability Convention of 1972, provides a foundation but lacks specific provisions for active debris removal. Key legal challenges include:

- Jurisdiction and Ownership: Who has the right to approach and modify another nation’s defunct satellite? The Outer Space Treaty states that objects launched into space remain the property of the launching state. Removing such an object without explicit consent could be considered an act of “space trespassing” or even an attack. This poses significant legal questions, particularly when dealing with debris from defunct satellites belonging to nations that no longer exist or are unidentifiable.

- “Rules of Engagement”: How should close-proximity operations with uncooperative objects be governed? Establishing clear guidelines for rendezvous and capture operations is necessary to avoid misunderstandings or escalating tensions.

- Harm to Third Parties: Who is liable if a debris removal mission inadvertently causes further debris or damage to another operational satellite? The Liability Convention holds launching states responsible for damage caused by their space objects. Active capture missions introduce new layers of potential liability.

International consensus and the development of new legal frameworks are essential for progressing active debris removal.

As the issue of space debris continues to grow, innovative solutions are being explored, including the concept of active capture satellites designed to remove defunct satellites and debris from orbit. A related article discusses the ambitious multimedia efforts surrounding this topic, highlighting the importance of addressing space sustainability. For more insights on this initiative, you can read the full article here.

Future Outlook and Challenges

| Metric | Description | Typical Values | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Active Capture Satellites | Satellites currently operational for debris removal | 3 – 5 | Units |

| Capture Mechanism Types | Methods used to capture debris | Robotic Arms, Nets, Harpoons, Tethers | Types |

| Maximum Debris Size Captured | Largest debris piece that can be captured | Up to 5 | meters |

| Operational Altitude Range | Orbit altitudes where satellites operate | 400 – 1200 | kilometers |

| Average Capture Time per Debris | Time taken to capture one piece of debris | 1 – 3 | days |

| End-of-Life Disposal Method | How captured debris is removed from orbit | Deorbiting, Controlled Reentry | Methods |

| Typical Satellite Mass | Mass of active capture satellites | 500 – 1500 | kilograms |

| Power Source | Energy source for satellite operations | Solar Panels | Type |

| Mission Duration | Expected operational lifespan | 1 – 3 | years |

| Success Rate | Percentage of successful debris captures | 70% – 90% | Percent |

Active capture satellites represent a critical tool in the long-term management of space debris. While significant progress has been made in demonstrating the feasibility of certain capture technologies, widespread implementation faces considerable challenges.

Autonomous Operations and AI

The complexity of rendezvous and capture, particularly with rapidly tumbling or uncooperative targets, necessitates a high degree of autonomy. Current remote control operations are limited by communication delays and bandwidth. Future missions will rely heavily on artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for:

- Real-time Decision Making: Adapting to unexpected target behavior or environmental changes.

- Sensor Fusion: Integrating data from multiple sensors (lidar, radar, optical) to build a comprehensive understanding of the debris’s state.

- Path Planning and Collision Avoidance: Generating safe and efficient trajectories around and toward the target.

- Fault Detection and Recovery: Ensuring the capture satellite can operate reliably even with minor system malfunctions. AI-driven systems could learn from previous capture attempts, refining their strategies over time.

Scalability and Cost-Effectiveness

For active debris removal to be effective, it needs to be scalable. Removing one or two objects per year will not be sufficient to address the growing population of debris. The cost of individual missions, currently in the hundreds of millions of dollars, is a major barrier to widespread deployment. Future efforts must focus on:

- Modular Designs: Developing standardized components and platforms that can be adapted for different target types.

- Multi-Object Capture: Designing satellites capable of capturing and deorbiting multiple pieces of debris in a single mission, perhaps by repeatedly descending to lower orbits or deploying smaller “scavenger” craft within a larger mission architecture.

- Reusability: Exploring concepts where active capture satellites can be refueled or repurposed for multiple missions, reducing the per-object cost.

- Economies of Scale: As the technology matures and more missions are conducted, costs are expected to decrease, similar to the trajectory of satellite launch costs.

Ethical Considerations

Beyond the practicalities, active debris removal raises ethical questions:

- “Dual-Use” Technology: The very technologies used for active debris removal – rendezvous, capture, and deorbiting – could theoretically be repurposed for anti-satellite warfare, leading to concerns about the weaponization of space. This necessitates transparency and international verification mechanisms.

- Environmental Impact of Re-entry: While most debris incinerates harmlessly upon re-entry, the increasing number of larger objects could lead to concerns about atmospheric pollution or the potential for surviving fragments to reach the ground.

- Space Preservation: Some argue that certain historic artifacts of space exploration, even if defunct, should be preserved rather than deorbited. Balancing the need for a clean orbital environment with the historical significance of certain objects is a delicate act.

These considerations highlight the need for international dialogues and the development of responsible guidelines to govern active debris removal operations. The journey to a sustainable orbital environment is long and arduous, requiring innovation, collaboration, and a shared commitment to preserving humanity’s access to space.

FAQs

What is space debris and why is it a problem?

Space debris consists of defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, and fragments from disintegration or collisions in Earth’s orbit. It poses a risk to operational spacecraft and the International Space Station due to potential high-speed collisions.

What are active capture satellites?

Active capture satellites are specialized spacecraft designed to rendezvous with, capture, and remove space debris from orbit. They use technologies such as robotic arms, nets, harpoons, or magnetic systems to secure debris for deorbiting or relocation.

How do active capture satellites remove space debris?

Once an active capture satellite locates and approaches a piece of debris, it uses its capture mechanism to secure the object. The satellite then either deorbits the debris to burn up in the atmosphere or moves it to a less congested orbit, reducing collision risks.

What are the challenges in deploying active capture satellites?

Challenges include accurately tracking and approaching fast-moving debris, safely capturing irregularly shaped or tumbling objects, managing the satellite’s own debris risk, and ensuring cost-effectiveness and reliability of the removal mission.

Are there any active capture satellite missions currently in operation?

Several experimental and demonstration missions have been launched to test active debris removal technologies, such as the RemoveDEBRIS mission by the European Space Agency. However, large-scale operational debris removal using active capture satellites is still in development.