Nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP) represents a potential paradigm shift in space travel, offering significantly reduced transit times for crewed missions to Mars and other deep-space destinations. This technology harnesses the immense energy released from nuclear fission to heat a propellant, expelling it at high velocity to generate thrust. Unlike conventional chemical rockets, which rely on the chemical energy stored in propellants, NTP systems leverage the far greater energy density of nuclear fuel. This fundamental difference translates into higher exhaust velocities and, consequently, more efficient propulsion. The implications for long-duration space missions, particularly those with human crews, are profound, as shorter travel times directly reduce exposure to cosmic radiation and microgravity, and lessen the overall logistical burden.

At its core, an NTP system operates on a straightforward principle: using a nuclear reactor to heat a working fluid. This fluid, typically liquid hydrogen, is then expanded through a nozzle to produce thrust. Imagine a high-performance jet engine, but instead of burning kerosene, it uses the sustained heat from nuclear fission.

Reactor Core Design

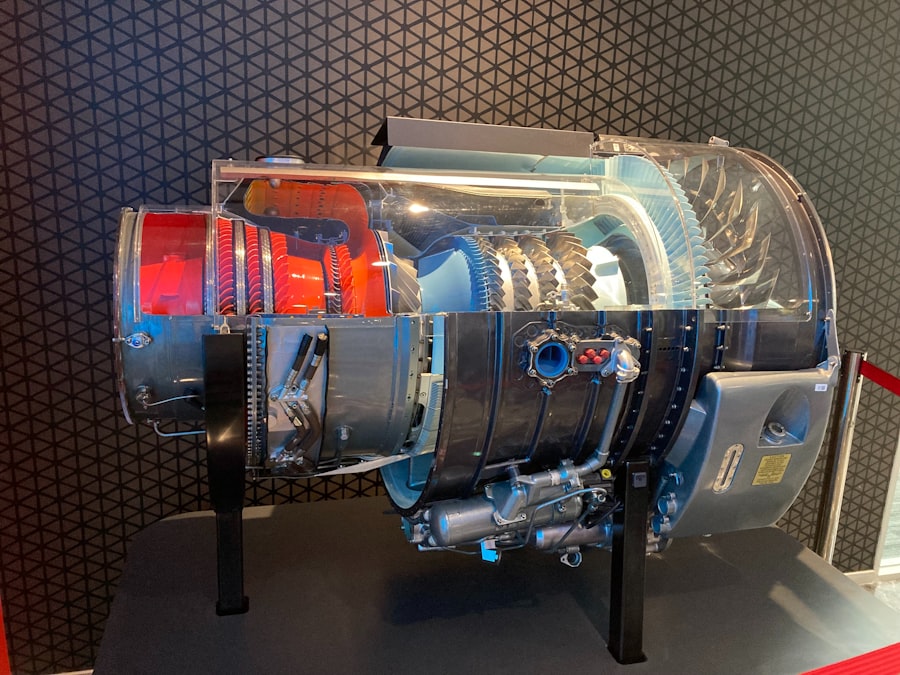

The heart of any NTP system is its nuclear reactor. This reactor is designed to achieve sustained fission reactions at extremely high temperatures. The choice of reactor materials and fuel form is critical.

Solid Core Reactors

Solid core reactors are the most thoroughly researched and developed NTP concept. In these designs, uranium fuel is embedded within a solid matrix, often a ceramic or refractory metal composite. These materials are chosen for their ability to withstand the extreme temperatures generated by the fission process, typically reaching 2,500 to 3,000 Kelvin (approximately 4,000 to 4,900 degrees Fahrenheit). The liquid hydrogen propellant flows through channels or interstitial spaces within this heated core, absorbing thermal energy before being expelled.

Liquid Core Reactors

Liquid core reactors, a more advanced and less mature concept, envision a reactor where the nuclear fuel itself is in a molten state. This design theoretically allows for even higher operating temperatures and exhaust velocities, as the limitations imposed by solid material melting points are circumvented. However, the engineering challenges associated with containing and managing a highly radioactive molten fuel at such temperatures are substantial.

Gas Core Reactors

Gas core reactors represent an even more ambitious concept, where the nuclear fuel is in a gaseous plasma state. These designs promise the highest performance characteristics, with exhaust velocities approaching those of electric propulsion, but at much higher thrust levels. The challenges of creating and maintaining a stable plasma of nuclear fuel, while preventing its contamination of the propellant, are formidable.

Propellant Selection

The choice of propellant significantly impacts NTP performance. Ideally, a propellant should have a low molecular weight to maximize exhaust velocity for a given temperature.

Liquid Hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen (LH2) is the primary propellant candidate for NTP systems. Its very low molecular weight (H2) makes it an excellent choice for achieving high exhaust velocities when heated. Furthermore, hydrogen is relatively abundant in the universe, though its cryogenic storage requirements (extremely low temperatures) pose significant engineering challenges for long-duration missions.

Exhaust Nozzle

The heated propellant is then expanded through a de Laval nozzle, similar to those used in chemical rockets. The nozzle converts the high-pressure, high-temperature gas into a high-velocity jet, generating thrust. The design of this nozzle is optimized to maximize the efficiency of this conversion.

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) has emerged as a promising technology for expediting missions to Mars, offering the potential for faster travel times and increased payload capacities. For those interested in exploring the broader implications of advanced propulsion systems, a related article discusses the evolution of technology and innovation in space exploration, highlighting key figures and milestones in the industry. You can read more about this fascinating topic in the article found at here.

Performance Advantages Over Chemical Propulsion

NTP offers substantial performance advantages over traditional chemical rockets, particularly for missions requiring significant changes in velocity (delta-v). Think of it as the difference between a conventional car engine and a high-performance electric motor – both move you forward, but one does so with far greater efficiency and power for its fuel.

Higher Specific Impulse

The most critical metric for rocket engine efficiency is specific impulse (Isp). Isp measures the amount of thrust produced per unit of propellant consumed per unit of time. Chemical rockets typically achieve specific impulses in the range of 400 to 460 seconds. NTP systems, in contrast, are projected to achieve specific impulses of 800 to 1,000 seconds, effectively doubling the efficiency. This means that for the same amount of propellant, an NTP engine can generate thrust for a much longer duration, or achieve a much higher final velocity.

Reduced Transit Times

The higher specific impulse directly translates into significantly shorter transit times for deep-space missions. For a crewed mission to Mars, this can mean reducing a nine-month journey to as little as three to four months. This reduction is not merely a convenience; it fundamentally alters the risk profile of the mission.

Radiation Exposure

Shorter transit times reduce the crew’s cumulative exposure to cosmic radiation and solar particle events, both of which pose health risks beyond Earth’s protective magnetosphere.

Microgravity Effects

Prolonged exposure to microgravity leads to bone demineralization, muscle atrophy, and cardiovascular deconditioning. A shorter journey lessens the duration of these detrimental effects, reducing the need for extensive countermeasures and facilitating crew recovery upon arrival.

Logistical Demands

Less time in transit means less food, water, and consumables need to be carried, reducing the overall mass of the spacecraft and lowering launch costs.

Increased Payload Capacity

Alternatively, for the same transit time, NTP systems can carry a substantially larger payload. This capability allows for more scientific equipment, more robust life support systems, or greater reserves for contingencies.

Historical Development and Research

The concept of nuclear propulsion for space travel dates back to the early days of the space age, with significant research and development efforts in the United States.

Project Rover (1955-1973)

Project Rover was a U.S. government program initiated in 1955 to develop nuclear thermal rocket technology. This extensive program involved the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the NASA-managed Nuclear Rocket Development Station (NRDS) in Nevada.

Kiwi Series

The Kiwi reactor series, named after the flightless bird to signify its ground-test-only nature, focused on developing the reactor core components. Numerous reactors were successfully tested, demonstrating the viability of the concept.

Phoebus Series

The Phoebus reactors were larger and more powerful designs, pushing the boundaries of reactor size and heat output.

NERVA (Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application)

NERVA was the culmination of Project Rover, aiming to develop flight-rated nuclear rocket engines. The NERVA program successfully built and ground-tested multiple engines, including the XE engine, which demonstrated its reusability and throttling capabilities. However, due to changing political priorities and budget constraints, Project Rover and NERVA were ultimately canceled in 1973, despite significant technical success.

Post-Cold War Efforts

Following the Cold War, intermittent interest in NTP resurfaced, driven by renewed aspirations for human missions to Mars. Various studies and small-scale research projects have continued to explore the technology, aiming to leverage advancements in materials science and reactor design.

Challenges and Considerations

Despite the compelling advantages, the development and implementation of NTP systems face significant technical, regulatory, and public perception challenges.

Technical Hurdles

Several engineering hurdles must be overcome to realize operational NTP systems.

High-Temperature Materials

The reactor core operates at extreme temperatures, requiring materials that can withstand these conditions while maintaining structural integrity and resisting corrosion from the hot hydrogen propellant. Advanced ceramics, refractory metals, and composite materials are constantly being researched to improve performance and longevity.

Cryogenic Propellant Storage

Liquid hydrogen must be stored at extremely low temperatures (-253°C or -423°F). Maintaining these cryogenic conditions for extended periods in space, especially during coasting phases, presents a significant engineering challenge, requiring highly efficient insulation and boil-off mitigation strategies.

Reactor Control and Restart

Precise control of the nuclear fission reaction, including throttling capabilities for different thrust levels and the ability to restart the reactor multiple times in space, is critical for mission flexibility and safety.

Radiation Shielding

To protect the crew and sensitive electronics from the radiation emitted by the reactor, substantial shielding is required. This shielding adds mass to the spacecraft, which must be carefully balanced against propulsion performance. Innovative shielding designs, perhaps incorporating the propellant tanks themselves, are being investigated.

Safety and Environmental Concerns

Public perception and regulatory approval are significant aspects of NTP development, largely due to concerns associated with nuclear technology.

Launch Safety

The primary safety concern revolves around the potential for a nuclear accident during launch or in Earth orbit. An uncontained reactor core could release radioactive material into the atmosphere. Current designs typically envision launching the reactor in a “cold” or subcritical state, only activating it once the spacecraft is in a safe, stable orbit, far from Earth.

End-of-Life Disposal

Determining a safe and environmentally responsible method for disposing of a spent nuclear reactor at the end of its operational life is crucial. Options include disposal in a deep-space trajectory or controlled reentry with atmospheric dispersal of non-radioactive components (though this is less desirable for radioactive parts).

Public Acceptance

The “nuclear” label often evokes fear and skepticism. Public education and transparent communication about the safety measures and benefits of NTP are essential to gain acceptance for its development and use.

Policy and Regulation

International treaties and domestic regulations govern the use of nuclear technology in space. Adherence to these frameworks, particularly the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits placing nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit, is paramount. Developing robust regulatory frameworks for the safe operation and disposal of NTP systems is essential.

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) has the potential to significantly reduce travel time for missions to Mars, allowing for more efficient exploration of the Red Planet. This innovative technology harnesses the power of nuclear reactions to heat propellant, providing a much higher specific impulse compared to conventional chemical rockets. For those interested in advancements that enhance our technological capabilities, a related article discusses the latest innovations in power and performance, which can be found here. By leveraging such cutting-edge technologies, we can pave the way for faster and more ambitious space missions.

Future Prospects for Mars Missions

| Metric | Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) | Chemical Propulsion |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Impulse (Isp) | 800-1000 seconds | 450 seconds |

| Thrust | High (comparable to chemical rockets) | High |

| Transit Time to Mars | 3-4 months | 6-9 months |

| Propellant Efficiency | Approximately twice as efficient | Standard efficiency |

| Mission Payload Capacity | Increased due to higher efficiency | Lower compared to NTP |

| Operational Temperature | 2500 K (approximate reactor core temperature) | Varies, generally lower |

| Radiation Concerns | Requires shielding and safety protocols | Minimal |

| Development Status | Experimental and testing phase | Established technology |

Despite the challenges, the potential of NTP to revolutionize space travel, particularly for human missions to Mars, continues to fuel research and development efforts.

Reduced Mission Duration

The most compelling advantage remains the drastic reduction in transit times. A three to four-month journey to Mars compared to nine months significantly lessens the physiological and psychological toll on astronauts, making such missions more feasible and safer. Imagine the difference in embarking on a three-day car trip versus a week-long one; the shorter trip is inherently more manageable and less taxing.

Increased Mission Flexibility

NTP allows for more flexible mission profiles, including larger launch windows and the ability to carry more scientific instruments and supplies. This increased capability can enable more ambitious exploration objectives and improve the resilience of missions to unforeseen events.

Stepping Stone to Further Exploration

Successful implementation of NTP for Mars missions could pave the way for even more ambitious human exploration efforts to the outer solar system, where the limitations of chemical propulsion become even more pronounced. The efficiency gains could open up destinations that are currently beyond the practical reach of human explorers.

Terrestrial Spin-offs

Research and development in NTP could also yield spin-off benefits for terrestrial applications, particularly in advanced materials science, high-temperature engineering, and reactor technology. The innovations driven by the demands of space exploration often find their way back to improve life on Earth.

In conclusion, nuclear thermal propulsion offers a pathway to fundamentally alter the speed and scope of human space exploration. While significant technical, safety, and regulatory hurdles remain, the potential benefits—shorter transit times, reduced crew risk, and increased mission capability—underscore its importance in the future of deep-space travel. The journey to Mars remains a marathon, but NTP has the potential to turn it into a high-speed sprint.

FAQs

What is Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP)?

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion is a type of spacecraft propulsion that uses a nuclear reactor to heat a propellant, typically hydrogen, which then expands and is expelled through a rocket nozzle to produce thrust. This method offers higher efficiency compared to traditional chemical rockets.

How does Nuclear Thermal Propulsion speed up Mars missions?

NTP systems provide greater thrust and higher specific impulse than chemical rockets, allowing spacecraft to travel faster and more efficiently. This reduces the travel time to Mars, potentially cutting the journey from about nine months to around three to four months.

What are the advantages of using NTP for space exploration?

NTP offers several advantages, including increased propulsion efficiency, reduced travel time, and the ability to carry heavier payloads. These benefits can improve mission safety, reduce astronaut exposure to space radiation, and enable more ambitious exploration missions.

Are there any challenges or risks associated with Nuclear Thermal Propulsion?

Yes, challenges include the development and testing of safe and reliable nuclear reactors for space, managing radioactive materials, and ensuring environmental safety during launch and operation. Additionally, technical complexities and high costs are significant considerations.

Has Nuclear Thermal Propulsion been tested or used in space missions before?

While NTP technology was extensively researched and tested during the 1960s and 1970s under programs like NASA’s NERVA, it has not yet been used in an actual space mission. Current efforts are focused on developing and demonstrating NTP systems for future Mars missions.