Automated docking systems for satellites are critical technologies enabling complex orbital operations. These systems facilitate the rendezvous and physical connection of two independent spacecraft without direct human intervention in the final stages. Such capabilities are foundational for modular space station assembly, on-orbit servicing, deep space exploration architectures, and potential in-situ resource utilization. The evolution of these systems reflects decades of advancements in robotics, sensor technology, and control theory.

The concept of spacecraft rendezvous and docking emerged during the nascent stages of space exploration. Initially, these maneuvers were performed manually or with significant ground control input, relying heavily on human precision and real-time telemetry.

Manual Docking and its Limitations

Early Soviet and American space programs demonstrated the feasibility of bringing spacecraft together.

- Vostok/Voskhod Program (Soviet): While early missions focused on single-spacecraft orbital flights, the groundwork for rendezvous was laid with theoretical studies.

- Gemini Program (United States): The Gemini missions, particularly Gemini 8 with Neil Armstrong and David Scott, achieved the first successful orbital docking with an Agena target vehicle in 1966. This was a manually controlled operation, demanding intense focus and skill from the astronauts. Subsequent Gemini missions refined these techniques.

- Apollo Program: Docking became a routine, albeit critical, procedure for the Apollo command module to connect with the lunar module. Again, these were largely manual operations, guided by visual cues and instrumentation.

The inherent limitations of manual docking, such as reliance on human sensory input, susceptibility to fatigue, and the need for extensive training, quickly became apparent. For future large-scale space infrastructure, a more automated approach was essential.

Transition to Automated Rendezvous

The transition from manual to automated rendezvous and docking (AR&D) began with a focus on mitigating human involvement and increasing reliability.

- Soyuz Program (Soviet/Russian): The Soyuz spacecraft incorporated early forms of rendezvous automation. The Igla and later KURS systems provided automated guidance for rendezvous, significantly reducing astronaut workload during approach. While the final docking sequence could be supervised by cosmonauts, the automated capabilities were a cornerstone of their long-duration space station programs.

- Progress Spacecraft (Soviet/Russian): The uncrewed Progress resupply vehicles, designed to dock with Salyut and later Mir and the International Space Station (ISS), were among the first fully automated vehicles where docking was routine and uncrewed. Their success demonstrated the viability and reliability of automated systems.

Automated docking systems for satellites represent a significant advancement in space technology, enabling more efficient and precise operations in orbit. For those interested in exploring related topics, a comprehensive article discussing the latest innovations and expert reviews in this field can be found at Trusted Reviews. This resource provides valuable insights into the development and implementation of these systems, highlighting their impact on satellite missions and future space exploration endeavors.

Core Components and Technologies

Automated docking systems are complex integrations of hardware and software, working in concert to achieve precise alignment and connection. Think of it as a robotic surgeon, meticulously aligning two separate entities with microscopic precision, albeit on a much larger scale.

Guidance, Navigation, and Control (GNC)

The GNC system is the brain of the docking process. It processes sensor data, determines the spacecraft’s state relative to the target, and issues commands to propulsion and attitude control systems.

- Guidance: This function determines the desired trajectory and velocity profile for the docking maneuver. It calculates the optimal path to approach the target vehicle, often following a predefined corridor to avoid collision and minimize fuel consumption.

- Navigation: Navigation involves determining the precise position and orientation of the active spacecraft relative to the passive target. This relies heavily on sensor fusion.

- Control: The control system executes the commands generated by the guidance system. It utilizes thrusters (either monopropellant or bipropellant) and reaction wheels to adjust the spacecraft’s attitude and translation. Proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers and more advanced adaptive control algorithms are commonly employed to ensure stable and precise movements.

Sensing and Perception Systems

These systems provide the “eyes” and “ears” for the automated docking process, delivering crucial information about the relative state of the two spacecraft.

- Kinematic Sensors:

- GPS/GNSS Receivers: For long-range rendezvous, differential GPS (DGPS) or global navigation satellite system (GNSS) receivers provide highly accurate relative position data, often down to meter-level precision.

- Radar: Pulsed or continuous wave radar systems provide range and relative velocity information, particularly useful in the intermediate range where optical sensors might be less effective due to lighting conditions or distance.

- Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging): Lidar systems use laser pulses to create detailed 3D maps of the target, providing precise range and relative orientation data, especially crucial in the final approach phase.

- Optical Sensors:

- Cameras (Visible Light and Infrared): Standard cameras are used for visual tracking of fiducial markers on the target vehicle. Machine vision algorithms process these images to determine relative position and attitude. Infrared cameras can be beneficial in low-light conditions.

- Proximity Sensors: These are short-range sensors, often employing ultrasonic, laser, or eddy current principles, used in the final moments before contact to ensure correct alignment and detect any last-minute deviations.

- Force-Moment Sensors: Integrated into the docking mechanism itself, these sensors detect contact forces and torques during the initial physical connection, providing feedback for latching and securing.

Automated docking systems for satellites are revolutionizing space operations, enhancing the efficiency and safety of satellite servicing and assembly in orbit. For a deeper understanding of the technological advancements driving these innovations, you can explore an insightful article that discusses the broader implications of emerging technologies in the field. This resource provides valuable context on how automated systems are shaping the future of space exploration. To read more about these developments, visit this article.

Docking Mechanisms

The physical interface that connects the two spacecraft. Think of them as sophisticated grappling hooks that also seal off the internal environment.

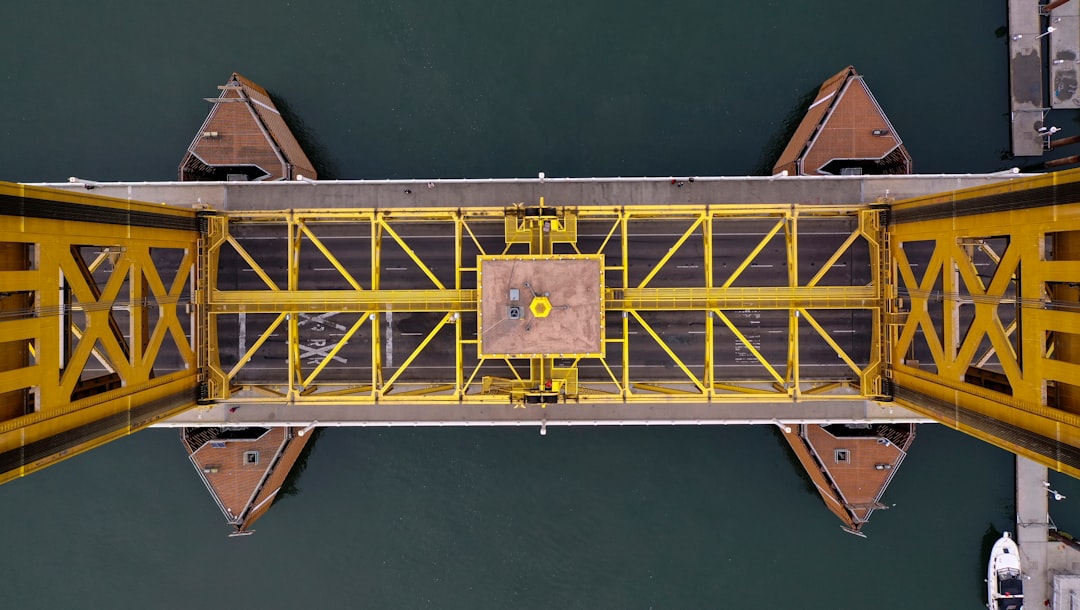

- Androgynous Peripheral Docking System (APDS): Used by the International Space Station for its Common Berthing Mechanisms (CBMs) and some visiting vehicles. It features a mechanism that can act as both the active and passive side. The CBMs often require robotic arm assistance to berth, rather than direct thruster-driven maneuvers.

- Probe-and-Drogue System: An older, simpler design where a probe (a male part) extends from the active spacecraft and inserts into a drogue (a female conical receptacle) on the passive spacecraft. Latches secure the connection. This design was used extensively in the early Soyuz and Apollo programs.

- Low-Impact Docking System (LIDS) / International Docking System Standard (IDSS): These next-generation, universally compatible designs aim to reduce contact forces and provide a softer, more robust connection. They feature soft-capture mechanisms that mitigate impact, followed by hard-capture mechanisms that form a pressure seal. NASA’s International Docking Adapter (IDA) uses this standard.

- Berthing Mechanisms: While related, berthing often implies the use of a robotic arm to mechanically attach two spacecraft, rather than a propulsive docking maneuver. The ISS utilizes both docking (e.g., Soyuz, SpaceX Dragon, Cygnus) and berthing (e.g., HTV, some Dragon cargo) ports.

Operational Phases of Automated Docking

The docking process is typically broken down into distinct phases, each with its own set of requirements and operational parameters. Imagine a dancer performing a complex routine, each step meticulously planned and executed.

Far-Field Rendezvous

This phase involves bringing the active spacecraft into the general vicinity of the target.

- Orbital Phasing: The active spacecraft performs maneuvers to match the target’s orbit and achieve a relative position ahead or behind the target, typically several hundred kilometers away.

- Trajectory Correction Manoeuvres (TCMs): Small thruster firings are executed to refine the trajectory and adjust orbital parameters based on navigation data from ground control and onboard GNSS receivers.

Proximate Operations and Approach

As the active spacecraft draws closer, more sophisticated sensors and control algorithms come into play.

- Terminal Guidance: Once within a few kilometers, optical sensors, radar, and lidar begin to provide precise relative navigation data. The guidance system calculates the optimal approach trajectory, often a V-bar (velocity vector) or R-bar (radial vector) approach, designed for safety and fuel efficiency.

- Hold Points and Abort Zones: The approach path typically includes several “hold points” where the spacecraft pauses to verify its state and readiness before proceeding further. “Abort zones” define regions where pre-planned escape trajectories are initiated if anomalies occur.

- Fly-Around Maneuvers: In some cases, the active spacecraft may perform a fly-around, circumnavigating the target to visually inspect it or to align with a specific docking port.

Contact and Latching

This is the moment of physical connection, where precision and robustness are paramount.

- Soft Capture: The active spacecraft slowly approaches the target until the docking mechanisms make initial contact. Low-impact designs feature “soft capture” rings or mechanisms that absorb residual kinetic energy and provide initial alignment.

- Hard Capture (Latching): Once soft capture is achieved, powered mechanisms (e.g., hooks, latches, or motor-driven seals) pull the two spacecraft together, forming a rigid, hermetically sealed connection. This process typically involves multiple redundant latches to ensure integrity.

- Leak Checks and Pressurization: After hard capture, internal systems perform leak checks to ensure the integrity of the pressure seal. If successful, the vestibule between the two spacecraft can be pressurized before hatch opening.

Challenges and Future Trends

Despite significant advancements, automated docking systems continue to evolve to address new challenges and enable more ambitious missions.

Technical Challenges

- Sensor Reliability in Varied Lighting: Space environments present extremes of light and shadow, which can challenge optical sensors. Developing robust algorithms that perform well in diverse illumination conditions is crucial.

- Relative Navigation Accuracy: Achieving sub-millimeter precision in relative position and attitude over long distances and diverse operational scenarios remains a driver for sensor and algorithm development.

- Fuel Efficiency and Thruster Jitter: Minimizing fuel consumption during docking is vital for mission longevity. Thruster firings, especially small impulse adjustments, can induce vibrations (“jitter”) that complicate precise alignment.

- Autonomous Decision-Making: While automated, many systems still rely on significant human oversight and intervention for anomaly resolution. Increasing onboard autonomy to handle unexpected events without ground interaction is a major goal.

- Space Debris: The increasing population of orbital debris poses a threat to both active and passive vehicles during rendezvous and docking. Collision avoidance maneuvers add complexity.

Future Applications and Trends

- On-Orbit Servicing and Assembly (OOS/OOSA): Automated docking is fundamental for refueling, repairing, upgrading, and assembling satellites in orbit. This promises to extend satellite lifespans and create larger, more capable space structures.

- Modular Space Stations: Future human habitats or scientific platforms could be assembled robotically from individually launched modules.

- In-Orbit Refueling: Extending the operational life of valuable assets by delivering propellant in orbit.

- Deep Space Rendezvous and Docking: Missions Beyond Earth orbit (e.g., to Mars, asteroids, or the Moon) will require AR&D capabilities where real-time ground control is impossible due to communication delays. This necessitates highly autonomous systems.

- Lunar Gateway: Future components of the Gateway around the Moon will rely on automated docking for assembly and resupply.

- Mars Sample Return: Docking in Mars orbit to transfer scientific samples collected from the Martian surface.

- Satellite Constellation Management: While not strictly docking, advanced AR&D technologies will contribute to proximity operations, formation flying, and de-orbiting services for large satellite constellations.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: Integrating AI and ML into GNC systems for enhanced autonomy, anomaly detection, and predictive maintenance. Neural networks could potentially process sensor data more effectively than traditional algorithms, leading to more robust performance in unstructured environments.

- Vision-Based Navigation Refinements: Progress in computer vision, particularly deep learning, can improve the ability of spacecraft to recognize target features, estimate relative poses, and perform robust navigation even with degraded visual data or in uncooperative scenarios.

Automated docking systems for satellites are a testament to human ingenuity in overcoming the challenges of the space environment. They represent intricate symphonies of engineering, bringing together disparate components with precision and reliability. As humanity ventures further into space and develops more complex orbital infrastructure, these systems will remain at the forefront of technological innovation, enabling the next generation of space exploration and utilization.

FAQs

What is an automated docking system for satellites?

An automated docking system for satellites is a technology that enables two spacecraft to connect or dock with each other without human intervention. It uses sensors, guidance algorithms, and control systems to align and join the satellites safely and precisely.

Why are automated docking systems important for satellite missions?

Automated docking systems are crucial because they allow for efficient assembly, refueling, repair, or upgrading of satellites in orbit. They reduce the need for manual control, minimize human error, and enable complex missions such as space station resupply or satellite servicing.

How do automated docking systems work?

These systems typically use a combination of radar, lidar, cameras, and other sensors to detect the relative position and orientation of the target satellite. Advanced algorithms process this data to guide the docking spacecraft, controlling thrusters and robotic arms to achieve a secure connection.

What are some challenges faced by automated docking systems?

Challenges include ensuring precise navigation in the microgravity environment of space, dealing with communication delays, avoiding collisions, and managing the mechanical complexity of docking mechanisms. Additionally, systems must be highly reliable to prevent mission failures.

Which satellites or missions have successfully used automated docking systems?

Automated docking has been successfully demonstrated in missions such as the Russian Progress cargo spacecraft docking with the International Space Station, the European Space Agency’s Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV), and more recently, commercial missions like SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft performing autonomous docking maneuvers.